by Dean Brandum

(As we return from our popcorn break)

PART FOUR: MAKING AN INDUSTRIAL MOUNTAIN INTO A MOLEHILL – PARAMOUNT’S DISASTROUS POSTWAR PERIOD.

By 1946 Paramount had established itself as market leader in the American film industry. In a year that was bountiful for nearly all studios (only United Artists suffered a loss), the company realised profits of $39.2 million, nearly double of its nearest rival, 20th Century Fox. This was a record for Paramount – in fact, it would take over 30 years for any film company to better that figure. (Finler 151)

Paramount’s success was based on a two factors: firstly, a well-crafted slate of features. For 1946 the studio had produced twenty-one films, of which perhaps only two could be classed as ‘super-specials’. The remainder were a mix of specials and programmers, all afforded the quality sheen of a well-honed production line. The slate also included three B-films, from the Pine-Thomas production unit. A wide range of genres were encompassed and the films starred a variety of the more popular performers of the period. (Eames 178-180) This formula had been perfected over many years, but 1946’s range of films appeared no more remarkable than a number of previous years, with no particular blockbuster hit accounting for such high returns. What enabled Paramount to achieve such profits can be attributed to the second factor – exhibition.

In 1945 Paramount owned (outright) 14 theatre chains comprising of 455 theatres, had controlling interests in another 775 and was a minority partner in another 275. Paramount could channel their product directly through their own cinemas, thereby collecting the entire gross, rather than just the rental, which is the amount customarily returned to distributors. Naturally, if the films are of a higher quality (ie: with greater audience appeal), the theatre’s revenues – and in turn the parent company’s – will increase exponentially. (Izod 118-120) In 1946 Paramount’s fortunes were aided immeasurably by Americans attending the cinema in record numbers. 82 million tickets were being sold per week, an amount consistent with the previous three years. (Finler 288) Now, with the Second World War won and service personnel having returned home and reunited with their families it would appear that with peace would flow even greater riches for America’s favourite ticket of entertainment.

Paramount’s holdings of 1500 cinemas were the most of any film-production company. In total, the studios owned approximately 3100 theatres, around 15% of the 18,000 operating in 1946. Overall this may have seemed a small percentage, but in terms of theatre value, the studios controlled 70% of the lucrative first run houses in American cities with populations of 100,000 or more and 60% of towns 25-100,000 in size. (Dick 37-9) The major studios had formed a business cartel with their theatre holdings and their control of the market had squeezed all but the most tenacious independent operators out of the exhibition business. The position of power allowed the majors to be almost at the point of managing the entire system. Yet such a position was necessary for these companies. The combination of theatres and studios had resulted in a vast number of employees and huge amounts of capital invested in production. It was imperative that the exhibition arm offered – as close to possible – a guaranteed and obstacle-free means of screening these films to the greatest number of ticket buyers as possible. By 1946 a theatre-owning studio such as Paramount would have planned its slate of films well in advance, booking them to their screens and allocating dates for when each film was to play. Entire schedules and financial forecasts would be built around such a practice. With over 3000 staff employed on their 23 acre West Hollywood lot producing 125,000 feet of film per week, it was essential that the company ran smoothly and with as few obstacles as possible in getting their films seen by the public. (Dick 41)

During the war years Hollywood had co-operated with the U.S. government to produce films encouraging of the war effort and in this period the Justice Department anti-trust investigations, which had been brewing since 1938 were, if not officially suspended, then at least deferred. When international hostilities ceased they soon resumed in courtrooms of Washington. A 1946 ruling outlawed (again) the practice of block-booking and two years later the Supreme Court’s “Paramount Decree of 1948” finally outlawed the vertically integrated business model that had been underpinned the majors’ success (and dictated their business practices) for over 20 years. As previous chapters have explained, the legislation caused a complete restructuring of the motion picture industry and its methods of exhibition. (Izod 120-8) Each of the major studios would be effected and, in most cases, adversely. In 1958 RKO would close and by the late 1960s, excepting 20th Century Fox and Columbia, all the major studios would no longer exist as independent entities, having been swallowed into larger conglomerates, their entertainment brands now only part of a diverse portfolio.

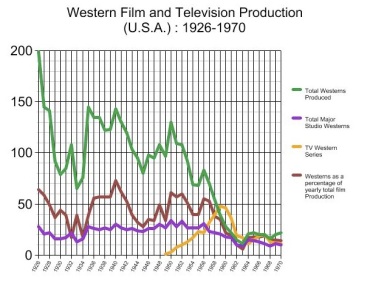

When taking into consideration that Paramount had the most theatres to lose and combined with the loss of audience in the 1950s and the rise of television, one would think that, when examining the following graph, that the studio did remarkably well to remain in constant profit throughout the period.

Yet the chart is misleading for a substantial proportion of the profits not from the revenue on film grosses (which were generally lacklustre) but through the sale of assets and corporate restructuring.

Yet the chart is misleading for a substantial proportion of the profits not from the revenue on film grosses (which were generally lacklustre) but through the sale of assets and corporate restructuring.

The most dramatic fall in profits came in 1949, the year after the divestiture order. In the unfamiliar role of having to negotiate nearly all of its distribution deals, the company suffered significantly. Yet the company was not entirely without its own options for exhibition. Although the studio controlled 1500 theatres, as a reward for early compliance with the ruling, Paramount was allowed a longer period of time to shed its holdings and to also retain 650 screens under its United Paramount Theatres banner. Although a separate company with no common stockholders it could still strike exclusive deals with the production company. Naturally, the theatres it chose to sell first were the least profitable in its stable (mostly later run houses). (Izod 163)

It was the revenue from the theatre sales that raised profits in 1950, aided by the returns from Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah, a release from late in the previous year which, with rentals of $9 million, was the studio’s highest grosser of the 1940s. Artistically, the company maintained a high standard for the first half of the new decade and attained peer plaudits by being nominated for the Best Film Academy Award each year between 1949-55 and winning 35 awards in the period. In the following fifteen years Paramount only won 15 and most of those were in minor, technical categories. (Finler 290-3)

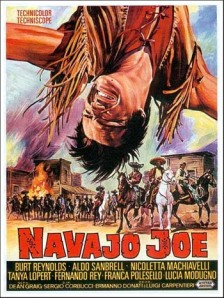

The drop in quality may be attributed to the drain of talent from the company as a number of famed filmmakers left the lot (including Alfred Hitchcock, William Wyler, Billy Wilder and George Stevens, disgruntled with budgetary cutbacks, inadequate marketing campaigns and a general attitude that Paramount management held little respect for their talents and abilities. (Dick 44-56). The cost-cutting measures also hampered Paramount’s ability to develop a pool of new actors and of the few that were popular with the public most, including Charlton Heston, Montgomery Clift and Burt Lancaster decided to further their careers elsewhere, in roles better suited to their talents. Only the comedy team of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis and musical star Elvis Presley (alternating with an MGM contract) were ongoing successes at Paramount into the 1960s. In turn, the studio turned to a number of aging, free-lancing actors to star in their films. However, the Paramount films of Clark Gable, Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney did little for the company’s financial fortunes and even less for its reputation as a vital and innovative filmmaking community. (Dick 44-63)

Many of the performers and directors who left Paramount, found their fortunes flourishing at United Artists, the least successful major studio of the War years. United Artists was never a true production company, instead it distributed the work of independent producers, with whom they shared the profits. During the classical Hollywood era this was a practice fraught with difficulties. Top talent was mostly aligned with studios and with a diverse group of films being handled it was difficult to maintain a continuity of releases. Yet in the mid-1950s, United Artists’ methods were clearly viewed as the future for the industry. With talent contracts being eliminated from the studios, stars, producers and directors began their own boutique companies to produce their own films. This offered them greater creative control over their careers but it also diverted their fees into the company, an option that incurred far less tax than that of a highly paid, salaried studio contract player. United Artists (now also involved in financing their releases) offered the strong incentive of near-autonomy to these independent companies and, with no overhead added on to budgets to cover operating expenses, budgets were kept at a level whereby both parties would prosper. (Gomery ‘Studio’ 191-227)

Paramount continued to retain an ‘in-house’ production operation of mostly staff producers overseeing projects. There were a couple of notable exceptions to this rule. The aforementioned Pine-Thomas B-unit developed projects with little interference from management, but with their low budgets and strong track record for profits they could be entrusted with virtual autonomy. The other was Hal Wallis. Poached from Warner Brothers in 1944 after he felt snubbed for lack of credit on the success of Casablanca (1943: Curtiz), Wallis joined Paramount with the promise of creative freedom and a very enticing financial arrangement. The belief was that Wallis could bring both prestige and commercial hits to the studio. Although he initially delivered the former with films such as Come Back Little Sheba (1952), The Rose Tattoo (1955) and The Rainmaker (1956), he tended to lose interest in artistic endeavour and instead concentrated on two of his discoveries, Jerry Lewis (firstly with Dean Martin) and Elvis Presley. (Dick 33-8) In box office terms, these were successful films, but due to the arrangement with Wallis, Paramount saw little in the way of profit. In fact, between 1954-1962 Wallis’ company had made $11 million on his films with Paramount. The studio managed a cut of under $800,000. (Dick 71-2) The reason for this was that Wallis was paid outright upon delivery of his films, whereas the studio had to make its money through distribution only, so revenues would trickle into the studio. At United Artists this was not a problem as there was little to no overhead to pay (the independent producers paid for the advertising), but for Paramount there was still an entire backlot to service, including thousands of employees. Thus Paramount were compelled to add an overhead of around 25% to any production (including independent) to cover such costs, a fee which dissuaded independent talent from working at the studio. (Dick 71-6)

In order to attract the talent, Paramount had to offer a better deal, one in which overhead was reduced (on certain productions) and separate (and often complex) deals were individually arranged. Overhead would continue to be charged (at a slightly higher rate) to in-house productions, which would then service the studio costs. As a result, Paramount began to attract the independent talent they longed for, but found they were producing films (both in-house and independent) simply to service the overhead. The following graph illustrates how Paramount ceased being a virtual in-house production studio and attempted to follow United Artists’ lead.

The process was slow and involved a continual wrestle with balancing overhead servicing with enticing talent to the company, especially when several deals with experienced producer-directors (Otto Preminger, Samuel Bronston) delivered costly failures. (Dick 59, 65)

The process was slow and involved a continual wrestle with balancing overhead servicing with enticing talent to the company, especially when several deals with experienced producer-directors (Otto Preminger, Samuel Bronston) delivered costly failures. (Dick 59, 65)

Yet somehow the company was still making money, garnering profits in the low millions each year. The sale of theatres in the early 1950s may attribute to the profits of the those years and Paramount finally found themselves with a true blockbuster with Cecil B. DeMille’s final film, The Ten Commandments, its $34 million in rentals placed it as the second most popular film of the decade and covering the losses of many of the company’s costly failures of 1956-7. (Finler 154) The impact of television upon Hollywood was profound and many companies had waged desperate battles to fight the new medium. Paramount however, had attempted to control television, firstly by owning a share in a television network (the failed DuMont, which eventually ceased broadcast in 1955), then through the expensive theatre-television concept by which movie audiences would be entertained with television broadcasts on the big screen before the film was projected. A cumbersome exercise, it was never embraced by audiences who preferred to keep a distance between the two media. This was also the case of their ambitious ‘Telemeter’ pay-television service by which customers would purchase broadcasts by dropping coins into a box, fitted to the television and wired to closed-circuit lines. For a company so seemingly attuned to the potential of television, it seems inconceivable that, in 1958, Paramount would sell almost all of their pre-1948 film catalogue to Universal-MCA, ignoring the usual practice of leasing films to networks for short periods. Although displaying a remarkable lack of foresight for future ancillary returns, Paramount received $50 million over three years which enabled them to maintain a small profit for the 1958-60 financial years. (White 145-164)

PART FIVE: ENTER LYLES

Paramount suffered a number of financially disappointing years in the post-war period, but 1962 was the worst of all. Hatari! was the studio’s biggest hit of the year and had the eighth highest rentals of any film that year. However, it was an expensive production and due to a generous arrangement with Howard Hawks, the film’s producer-director received half the profits and a handsome dividend was also paid to its star, John Wayne. The $7 million in domestic rentals may have looked impressive in boastful trade announcements, but resulted in little return for the studio. (Dick 70-3) Of the other releases that year, only The Man who Shot Liberty Valance (John Ford) was received with any critical enthusiasm, but could only manage 25th place among the top earners of the year. (‘rentals 1962’ 5) As had been the case for a number of years, the only reliable audience-pleasers for Paramount were Jerry Lewis, but his films were becoming too expensive to produce and advertise for the capped gross they could return and Elvis Presley, whose films may have been inexpensive, but as Hal Wallis productions the producer was seeing a greater cut that the studio. (Dick 73-8)

1963 offered little improvement, with only 14 releases for the year, just over half of a decade earlier. Escape from Zahrain (Ronald Neame) and Hell for Heroes (Don Siegel) premiered late in the previous year and went into a disastrous wide release in early of 1963. The studio’s biggest hit was The Nutty Professor, but as was becoming indicative of the company’s struggles, the increasing budgets approved to director-producer-star Jerry Lewis were inverse to his declining audience base. Initially Lewis had been provided with $150,000 to promote his film (decided on a basis of its expected gross) but Lewis demanded an extra half million, threatening to sever his ties with the company if they refused. With so few consistent performers at the studio, they had little choice but to acquiesce. The Nutty Professor was scheduled for limited first runs before a quick move to the second run circuit was only able to gross to a certain (although potentially profitable) cap. Yet as a result of the overspends, this quite popular (and seemingly small-scale) film found it impossible to make a profit, a fact the company was resigned to prior to its release. Similarly, Come Blow Your Horn (Bud Yorkin) was so steeped in profit-sharing arrangements with its producers and star (Frank Sinatra) that its moderate budget of $2.8 million (entirely financed by the studio) would only be covered by rentals of $6 million. That it managed such a take proved its hit status, but with negligible returns for Paramount. Even Hud (Martin Ritt), the company’s one critical success of the year was only moderately popular with audiences. (Dick 80-108)

That same year Paramount made their second foray into importing Italian peplum adventure films. Duel of the Titans (Sergio Corbucci) was picked up by sales executive Charles Boasberg for $70,000 when on a tour of European distribution operations. Following on from The Siege of Syracuse (Pietro Francisci) the following year, these films buffered the studio’s meagre distribution calendars and turned healthy profits for their miniscule investments. They were also a sign that Paramount were now prepared to follow the lead of the likes of American International Pictures by importing low budget genre product for the second-feature and second run market. (Eames 244)

When on his excursion to Italy Boasberg was continually asked by his sales divisions why there were few, if any westerns appearing on Paramount production slates. (‘oaters’ 3) Appendix #1 clearly illustrates why the western was no longer a staple of Hollywood production. Between 1960-1963 the only westerns to prove dominant box-office performers were excessively expensive productions that barely recouped their costs. Of the remaining western releases, few made any impact with audiences. In 1963 the western and Paramount had one thing in common: both were at their lowest ebb.

Yet in Italy the genre was far from dead – in fact it was more popular than ever. The resurgence in the genre was a trend felt across Europe and one which had led to a boom in western pulp literature, clothing and fashion. The dearth of new American westerns in cinemas had led to the defunct Republic’s back catalogue of B-westerns being purchased by enterprising distributors and re-released with commercial success. Even more innovative were some West German producers who began producing a series of smash-hit, locally made westerns featuring faded American performers. In Italy Buffalo Bill Hero of the West (1964: Massimo Dallamano) was in production and director Sergio Leone was in the process of arranging and Italian western of his own. With some foresight, American producer Lester Welch had already taken advantage of the European market (and its various beneficial co-production agreements) by shooting a pair of westerns back-to-back in Spain for international release by MGM. (‘U.S. Westerns’ 3)

Boasberg took the western request back to Paramount in Hollywood where initially the plan was to film a low-budget western in Italy, with American leads and key creative talent. However the location was changed to the studio’s Hollywood backlot. With so few films due to be shot on the studio premises, a large amount of space and employees were being under-utilised and by filming on the lot the studio could roll its much needed overhead into the production cost. Paramount also had a ready-made western main street available that had been constructed for the hit TV series Bonanza (1959-1972), for which NBC television rented Paramount’s studio space. As with the television series, any necessary location shooting for the proposed film would occur at nearby Vasquez Rocks National Park. (‘oaters’ 3)

Paramount management approached a long time mid-ranking associate producer named A.C. Lyles with the proposal. Lyles had worked with Paramount since the early 1930s, firstly at their theatres and then moving to the studio. In time he became head of publicity for Pine-Thomas and in the process learnt the rigours of how to make B-films on a tight budget and how to sell them to theatres. After Pine-Thomas ceased production, Lyles remained with Paramount, dividing his time between associate production on large scale films and independently producing his own for the company. He also had a stint in television, producing the first series of Rawhide in 1959. (Buscombe 327)

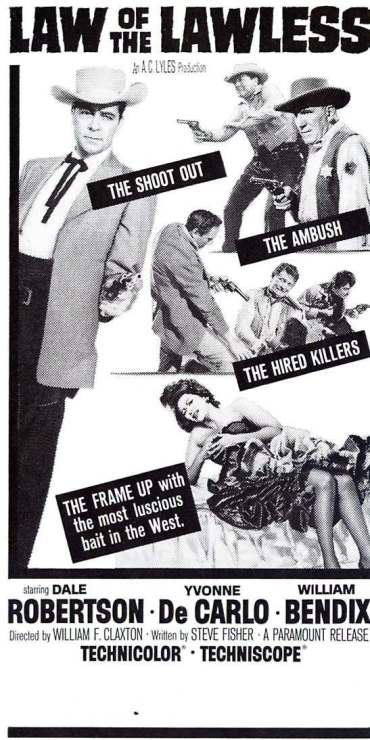

Told that they wanted a western as quickly and as cheaply as possible, Lyles immediately accepted, stating that he had a screenplay ready to film, written by veteran crime-pulp author Steve Fisher. Titled Invitation to a Hanging, it went into production in August of 1963 with a ten day shooting schedule and a budget of under $500,000. Lyles raised the finance himself, with Paramount due to purchase the finished product and A.C. Lyles productions taking a cut of any profits (perpetual copyright would be jointly held). (oaters 3)

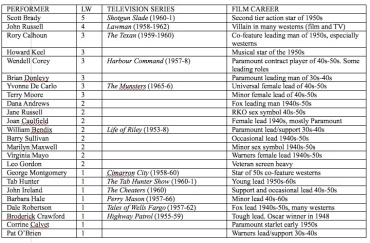

Rory Calhoun, a star of programmer western features in the 1950s and the short-lived The Texan (1959-1960) television series was chosen as the leading man, but was replaced shortly before filming commenced by Dale Robertson, whose career in westerns had followed a similar path to Calhoun’s except that his television series (Tales of Wells Fargo 1957-1962) had been far more successful. (Buscombe 380) The director was William F. Claxton, a former B-film editor who had worked successfully as a television director since the 1950s, including for a number of westerns, including Rawhide, Tales of Wells Fargo and Rifleman. (Buscombe 381) In fact it appears that Claxton, having spent most of 1963 filming episodes filming Bonanza, barely had to move his director’s chair to film Invitation to a Hanging. In a number of interviews Lyles has explained that no actor ever turned him down when he offered them a part in his films. He credits this with the friendships he had made through his long experience in the industry coupled with the fact that these performers were just hungry to work again – not for the money (Lyles paid them nominal fees) but for a return to the sort of roles and on-set family atmosphere they’d so enjoyed during the Hollywood’s classical era. Such an explanation may allude to an estimation that performers were of a certain vintage. And such a guess would be correct. Lyles populated his casts with fading stars of the classical era, along with recognisable character performers. Appendix #3 displays a full listing of those leading players plus any supporting actors who appeared in more than one of Lyles’ westerns. It shows that Lyles had a stock company regularly rotated through films. It would be churlish to doubt the producer’s claims that friendship was the key to the familiar casts, but there would probably have been the economic prerogative of the veteran performers being professional on set and not required many time (and stock)-consuming takes to complete their scenes. It also added to the ability to sell the films, with the familiar names impressively filling a cast list on advertising and creating immediate audience recognition. The casting was certainly recognised by critics, as their generally lukewarm responses were quite often enlivened with nostalgic fondness of the casting. Then successful television series that rejuvenated their careers. During the classical Hollywood era major studios would often use their B-units to train promising young talent. A.C. Lyles Productions may have not been a B-unit, but the fact that it very rarely featured young performers (or characters) among its casts is indicative of their utility at the time. These were stop-gap productions, made to fill soundstages , create overhead, exploit an overseas market opening and bolster domestic release schedules. Like Paramount itself, they looked to the moment, with thought of the future. Yet there is a trend evident in the careers of the many of the leading players. A second tier stardom in during the classical period but a loss of direction once they were forced to work freelance, followed by a successful television series that rejuvenated their careers. So although young talent rarely figured in Lyles’ productions, younger audiences would be familiar with the veterans’ recent television work, whilst their parents would be attracted by the stars of their youth.

Invitation to a Hanging was retitled Law of the Lawless after completion and released first in Italy in November of 1963. According to Lyles, by the time it has finished its Italian run it had recouped its negative cost. (Marks 43) The film was released domestically the following year, with the studio offering a number of methods to sell the production, including radio spots, TV trailers and the standard sets of lobby cards an posters, including a billboard-sized 24 sheet, usually reserved for blockbuster productions. The ad copy – provided as free press ‘stories’ for the print media, emphasised the film’s all star cast and its action-packed narrative. Over twenty admat options were available for print advertising, including one stating that Law of the Lawless had been held over for its fifth week. (pressbook 5) It is highly unlikely such an ad was ever used. The film’s premiere first-run engagement appearing to be in Los Angles beginning March 18th as a support to Paramount’s Son of Captain Blood, a European co-produced, low-budget swashbuckler that featured the gimmick of Sean Flynn, the son of Errol, in the titular role. According to Variety, business was ‘slow’ and the engagement only lasted a week. The lacklustre boxoffice was repeated as the double-feature made its way across eight Midwestern cities in first run engagements, including a multiple run at six Kansas City drive-ins, the engagement’s only healthy box-office returns.

It took Law of the Lawless five months to open in New York, without a first-run engagement and now supporting Robinson Crusoe on Mars (Son of Captain Blood did not appear in America’s largest city until the end of the year and in true co-feature style it had by then been dropped to the bottom of the bill). This new double feature was premiered in New York as part of Paramount’s ‘showcase’ presentation method, first used by the studio in June of that year for Love With a Proper Stranger (1963: Richard Mulligan). Sixteen screens were used and $98,000 was the week’s take. Compared to the slow returns during the film’s first run releases, this was hefty and quick injection into the distributor’s revenue stream. (‘Par takes turn’ 5)

And at this point of time, Paramount needed all the revenue they could find. Two years earlier the studio had committed to investing in The Fall of the Roman Empire, an Anthony Mann directed epic to be shot in Spain. Although Paramount management had concerns over the screenplay, they did not want to pass on a potential El Cid (1961) that had been a blockbuster hit for producer Samuel Bronston and Allied Artists, the company that financed it. Paramount paid $5 million for the North American distribution rights only – an amount that would have been nearly impossible to recoup, even if the film was a success. Such an argument remained moot as The Fall of the Roman Empire was a colossal disaster, netting under $2 million in rentals for the studio, with little of that left after paying for its expensive roadshow campaign. Paramount also had to endure a $3 million loss on Paris When it Sizzles, a romantic comedy starring William Holden and Audrey Hepburn. It was fortunate that the studio had entered a five-picture agreement with Joseph E. Levine and his Embassy production company. The first film from the deal, The Carpetbaggers, was among the year’s top money earners and allowed the company to show a modest profit for the year. Two years later, after delivering mostly hits and all of the salacious variety to the company, Levine was to depart fearing Paramount would collapse. Unable to convince him to stay, the company could only watch in disbelief as Levine’s moderately budgeted The Graduate saw his new distributor, Columbia, share in nearly $40 million of rentals from the year’s blockbuster hit. (Dick 67-91)

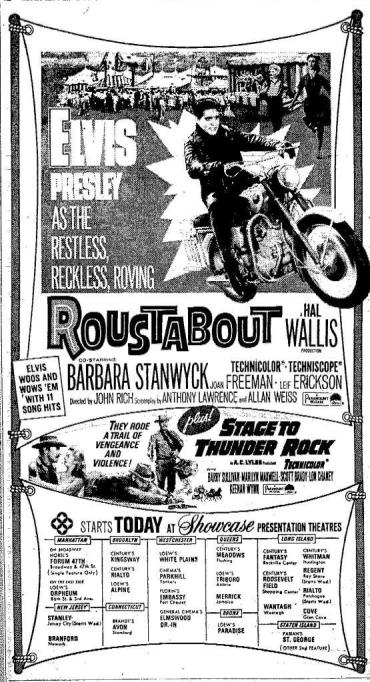

Even before Law of the Lawless had opened domestically, Lyles had another film completed, Stagecoach to Hell, made immediately after Paramount commissioned Lyles to produce a further four films, based on his first effort’s success in Europe. Retitled Stage to Thunder Rock, the second of Lyles’ westerns was once again directed by William F. Claxton, this time from a screenplay by Charles Wallace, a writer for television’s Tales of Wells Fargo and Zane Grey Theater.

Greeted with similar reviews to Lyles last film, Stage to Thunder Rock opened in June of 1964 simultaneously in Providence and Seattle, ironically as the support to Robinson Crusoe in Mars. Business was pallid, but it picked up substantially when the western was used to fill the bill on Roustabout (John Rich) in Los Angeles (managing two first-run weeks) and The Disorderly Orderly (for three weeks) in Portland. As had been proven since the late 1950s, Paramount’s only two reliable stars were Elvis Presley and Jerry Lewis and as was becoming evident, a supporting co-feature is only as successful as the main attraction at the top of the bill. For New York in November the successful Presley-Lyles combination was retained with a showcase presentation on 23 hardtops and a drive-in. For its only true first-run theatre in the group (The Forum on 47th Street), Roustabout screened without support.

In June of 1964 it was reported that A.C. Lyles was the only in-house filmmaker on Paramount’s lot. (‘quickened 3) Studio Production Head George Weltner hoped to add more, but it was now clear that the studio’s backlot was hopelessly under-ulitised and existing as rental space for television production. In 1962, Lew Wasserman, the head of Universal-International had wanted a new production space for his Revue television company. He approached Paramount with the notion of buying their entire backlot and transferring Universal’s feature production there, and moving the Revue arm onto the old Universal soundstages. Although the idea did appeal to some on the Paramount board, as it would leave the company without overhead and allow it to simply work as a distributor, the offer was declined. A year later Desilu Productions made similar overtures, to no avail. The studio was still proclaiming that while it was continuing to turn a profit there was no need to for such drastic action. Indeed the company did continue to make a profit, but in 1965 it was finally revealed that from 1962-65 all profits reported as from film revenue were infact losses topped up by $23 million worth of leasing the residual rights of failed films to television broadcasters and disguising the generous income as production revenue. After its premature and inexplicable sale of its pre-1948 catalouge to television in 1958, the company was now hanging on grimly to its post-1948 features and rationing them out on short term network broadcasts. Paramount was hoping in vain for the emergence of pay-television when company could cash in on these over-200 titles. Yet such a viable format was still a decade away and the stock of the company was growing at a negligible rate compared to the market value of the films in the vaults, ready for syndication and, for some of the lesser titles, in danger of losing their immediacy if not soon into the marketplace. When these details were revealed at a shareholders meeting in 1965, the corporate vultures began circling. (Dick 118-121)

In April of 1964 Lyles put Young Fury into production, with Christian Nyby directing. A former editor, Nyby is best remembered for his directing debut, The Thing From Another World (1951). Yet for Lyles it was probably more pertinent that Nyby was a regular director of Bonanza who had also had stints on Gunsmoke and Rawhide. Once again Steve Fisher contributed the screenplay. It was two months later that Paramount’s President Barney Balaban announced that the studio was “not in the business of making B-movies” (Mesca 13) and that he refused to dilute his slate with such fare, aiming for only productions in the A-bracket. Technically Babalan was correct as nobody in Hollywood was making true B-films, sold on a flat rate to exhibitors. However, as he was describing the studio’s upcoming productions, shareholders must have wondered how such upcoming titles as Lyles’ westerns, teen surf-capades The Girls on the Beach and Beachball, British horrors The Skull and Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors and the Italian peplum Revenge of the Gladiators counted as true A-bracket fare. (Eames 249-260) As all of these were pickups from independent producers, Paramount was not actually ‘making’ these films, but then again, almost all of their releases at this time had independent involvement as between 1963-65, of the 54 films released with the Paramount logo in the United States, only one was a completely in-house studio production.

Yet, with the big-budget fare not making money, it was these low-budget releases that were bringing in modest profits for the company (although far from offsetting the extravagant failures). In September that year it was reported that double features, having been out of favour with exhibitors since early in the decade, were now making a comeback. (Kalish ‘doubles’ 7) The popular showcase concept, that had now spread as to Los Angeles, Chicago and Boston, was acknowledged as the main reason for the popularity of the double feature, as was the multiple second-run release, ulitised for lower-budget and independent fare. With independents and studios all importing more foreign genre features than ever, there was a lucrative (although limited) market opportunity available.

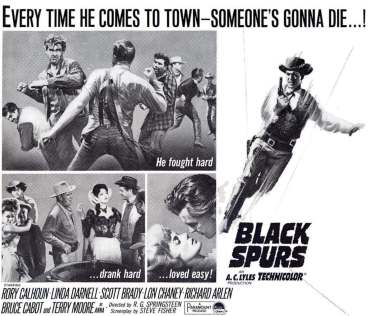

By the time Young Fury was released in the US in March of 1965 as a support to the science fiction thriller The Crack in the World, Lyles already had fulfilled his four-film contract by having a further two films completed. Black Spurs was filmed in September of 1964 and by the end of December, shooting had finished on Town Tamer.

Another from the prolific pen of Steve Fisher, Black Spurs was the first Lyles film to be directed by R. G. Springsteen, a prolific B-western director of the 1950s who had also recently spent time with Bonanza. Paramount took the unusual step of premiering Black Spurs in the US at New York’s grand 3665-seat Paramount theatre, the studio’s former flagship venue. Its $28,000 first week take may have seemed impressive, but was only rated as ‘fair’ by Variety. This was due to the fact that the western was playing as a support to a live ‘rock and soul show’ with tickets at substantially higher prices. Although a regular method of screening films in the 1920s-30s, live acts were rare accompaniment for feature films by the mid-1960s, although the Radio City Music Hall continued the tradition – and successfully too – with high profile studio productions after the stage show. Unfortunately for The Paramount theatre, Black Spurs was one of the last films to screen at the cinema and, after a period of closure, it was demolished the following year. In June, Black Spurs would enjoy a successful showcase run in Boston as a second feature to The Family Jewels, a Jerry Lewis director-star comedy and then in Los Angeles, on showcase with the John Wayne western The Sons of Katie Elder (Henry Hathaway). By the time Black Spurs was released in the United States, its female lead, Linda Darnell, had perished in a fire. Although she admitted her final film was a “ten day quickie”, it was her first feature in six years after battling alcoholism (Davis 247). Both The New York Times and Variety noted that it was the one notable aspect of the film. (17 & 9)

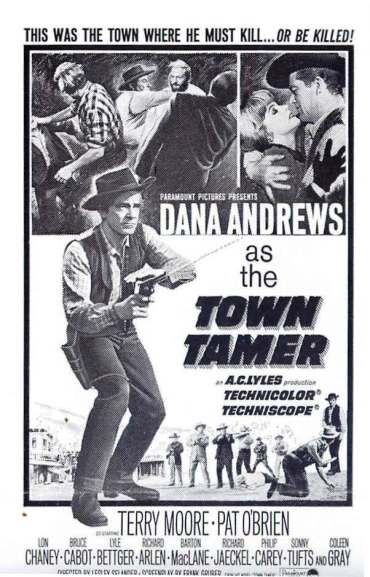

According to its pressbook, (5) “Action, excitement and robust drama makes Town Tamer an unforgettably exciting film of western adventure!” Lesley Selander, a director of mostly B-westerns since the early 1930s took directing duties on this production. Adapted by Frank Gruber from his own novel, it had apparently once been optioned as a project for Gary Cooper.

According to its pressbook, (5) “Action, excitement and robust drama makes Town Tamer an unforgettably exciting film of western adventure!” Lesley Selander, a director of mostly B-westerns since the early 1930s took directing duties on this production. Adapted by Frank Gruber from his own novel, it had apparently once been optioned as a project for Gary Cooper.

In the summer of 1965, Town Tamer was part of Paramount’s most ambitious showcasing endeavour. Having done a deal with the RKO chain of theatres in New York, the company announced a summer program of showcasing events as a way of displaying their renewed production vigour. Each engagement was to play in close to 100 theatres in what was the most saturated single city first-run yet.

The double features to screen were:

*Doctor Terror’s House of Horrors & The Girls on the Beach

*In Harms Way & Town Tamer

*The Family Jewels & Seven Slaves Against the World

*The Sons of Katie Elder & Revenge of the Gladiators (‘brief encounters’ 25)

Town Tamer’s showcase consisted of 94 screens (including 18 drive-ins), but it was reported that Lyle’s film was pulled from many engagement’s by the weekend due to the inordinate length of the program (In Harm’s Way had a running time of 165 mins).

Interestingly, Town Tamer’s next listed North American first run screening was supporting Universal’s Charlton Heston costume epic The War Lord (Franklin J. Schaffer) for two weeks in Denver (for excellent business). Paramount then used it as a second feature for the British-South African co-production of Sands of the Kalahari (Cy Enfield) but it finally made showcase in Boston and Seattle below the bill with the auctioneer Red Line 7000 (Howard Hawks).

By this time it was evident that Lyles’ westerns ran to a narrative and stylistic formula. From the viewing of seven of his productions, one can almost plot the narrative arc on a chart. Each film opens with an outdoor action sequence which introduces the hero. He may be fighting Indians (Red Tomahawk; Apache Uprising) or criminals (Johnny Reno; Buckskin). He then arrives in a town where he is treated suspiciously by some of the locals, with a street fistfight (Apache Uprising, Buckskin) or a barroom brawl occurring (Johnny Reno, Black Spurs, Hostile Guns). Tended to by a caring woman who is either a saloon worker or with a salacious past, the hero then must reluctantly take on a law-making role in the town, due to the weak, ineffectual sheriff being unable to control the villain. Eventually, in another location sequence, the hero and villain with have a chase / shootout / fistfight, with the hero winning. He then leaves town, usually accompanied by the woman.

With storylines that could be efficiently told in a tight 75 minutes, the Lyles westerns move out of the B-film length by adding superfluous sequences (such as trying to convince the female gambling hostess to part with her Gatling Guns in Red Tomahawk which she eventually agrees to with little explanation). Lyles films also include extraneous characters (such as the hired gun with a conscience in Buckskin and the convicts in Hostile Guns) who each require a backstory and provide it in lengthy dialogue-laden sequences. In fact, Lyles even noted in the Buckskin pressbook that he ensured every character had at least three strong scenes. (5)

Stylistically and technically, the Lyles films are grounded in a tele-visual sensibility. Most action occurs indoors on studio sets, with even a number of supposed exteriors being filmed on soundstages, its film stock and lighting poorly matched with the location-filmed establishing shots. There is something almost surreal about the stage-bound nature of many of these sequences, with several shadows being cast by performers as they stand on incorrectly lit sets, among lifeless shrubbery brought in from the prop-department. Scenes are blocked with such consistency that a two-way conversation in a room will have the characters move in a ritualistic manner around the room, in order to benefit the two cameras covering the sequence. With an establishing shot followed by a series of two-shots, a stationery conversation is given little visual flair. In one scene, in Johnny Reno, the gunman and saloon girl have a conversation that contains 23 cuts back and forth between two-shots, with only the establishing shot being used a second time in an effort to break the visual monotony.

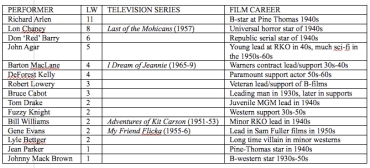

Indeed, the Lyles films appear to have been created in the editing room from the smallest amount of coverage possible. The following table compares five Lyles films with a number of other westerns – Paradise Canyon (1935: Carl Pierson); Dodge City (1939: Michael Curtiz); Storm Over Wyoming (1950: Lesley Selander) No Name on the Bullet (1959: Jack Arnold) and The Sons of Katie Elder (1965: Henry Hathaway). As each film was carefully viewed, the number of edits were recorded, as was the number of new camera set-ups within the film (those that had not occurred within the past three scenes). The number of edits is divided by the number of new set ups, resulting in an average number of edits per set-up. As the table illustrates, a B-western of the 1930s, one from 1950, big budget westerns from 1939 and 1965 and a standard town western co-feature from 1959 all manage to less frugal with their coverage. It must be noted that such a formula is not supposed to be an indicator of quality, but it does indicate that Lyles filmmakers got as much out of their limited coverage as possible and preferred as few set-ups as they could manage. The high average on his films would be due to the scene that was earlier described – so many characters, in so many conversations, with so much backstory and exposition to tell.

|

TITLE |

MINS |

EDITS |

NEW SETUPS |

AVERAGE EDITS PER SETUP |

|

Paradise Canyon |

52 |

553 |

318 |

1.73 |

|

Dodge City |

104 |

913 |

571 |

1.59 |

|

Storm over Wyoming |

58 |

618 |

345 |

1.79 |

|

No Name on the Bullet |

77 |

616 |

331 |

1.86 |

|

Law of the Lawless |

87 |

609 |

198 |

3.07 |

|

Sons of Katie Elder |

117 |

830 |

554 |

1.49 |

|

Apache Uprising |

87 |

613 |

312 |

1.96 |

|

Red Tomahawk |

82 |

782 |

304 |

2.57 |

|

Johnny Reno |

83 |

718 |

308 |

2.33 |

|

Hostile Guns |

90 |

691 |

309 |

2.23 |

The tele-visual blandness is offset by all the Lyles westerns being shot in Techniscope, a low cost, widescreen format which did not require special lens. Instead, the film stock was then enlarged to suit 2.35:1 projection. Much favoured by Italian western filmmakers due to its grainy aesthetic (caused by the lack of clarity in the enlarging process), Lyles was one of the first filmmakers to embrace the technology. (Holben 96-107)

In May of 1965 Lyles had his contract extended to a further ten films in 30 months. The report referred to a contract for “ten colour tinters”, which reflects their formulaic, production-line quality. (‘a.c. lyles’ 3) Apache Uprising (filmed in April of 1965) was the first of the new commission. Adapted by Harry Sanford and Max Lamb from their novel Way Station, R.G. Springsteen was directing again. However, after a four hardtop and two drive-in showcasing in Toronto supporting The Naked Prey in March of 1966, the film only received one more first run engagement, with the independent western Forty-Acre Feud. It was quickly followed into theatres by Johnny Reno, released in May of 1966 to a 6 Drive-in multiple in Toronto, second billed to Night of the Grizzly. In Detroit in July it had a week of good business supporting a musical live performance.

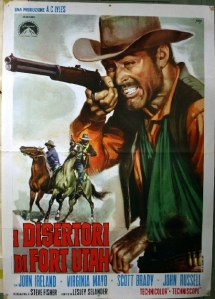

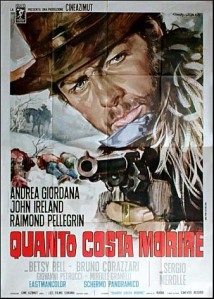

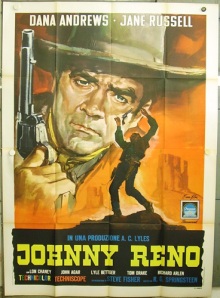

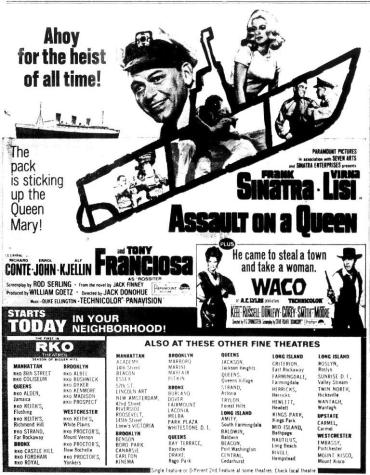

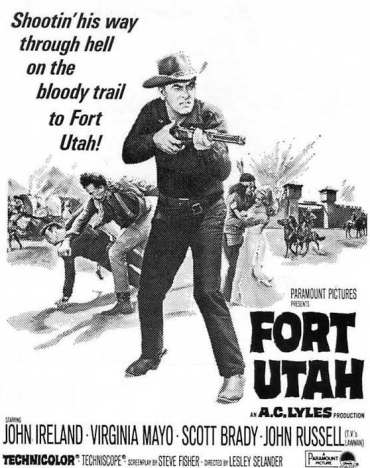

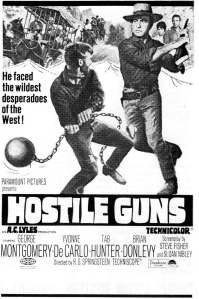

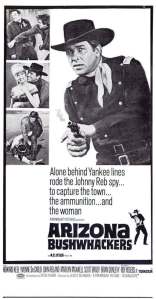

In March of 1966, Paramount was purchased by the oil company Gulf & Western, whose chairman saw the studio as an ideal component for his company’s conglomerate. Initially interested in the film library, he considering closing down the production unit and concentrating on just distribution. Robert Evans was appointed vice-president in charge of production and was given the seemingly impossible task of turning the studio into a money-making venture, allowing it a reprieve. At the shareholders’ meeting that year he stated that capitalisation was in place for a new series of expensive productions, including a number of European and British co-productions. The Lyles westerns would continue due to their European popularity. (‘evans’ 5) Indeed the western was still popular in Italy. It was reported in August that year that there were 24 westerns playing in Rome theatres, compared to only six in New York. The majority of these westerns were European productions and, insofar as their advertising, they were disguised as Hollywood product. The following four Italian one-sheet posters illustrate how, with their iconic imagery and promotion of American performers in the cast, it was difficult to tell the authentic Hollywood (Lyles) western from the European variant. (The films depicted are Fort Utah, Navajo Joe (1966: Sergio Corbucci), Johnny Reno and Cost of Dying (1968: Sergio Merolle).

Yet the market there was changing, with a particular sadism and excessive sex and violence evident in the Italian westerns as they reached a saturation point in the Italian industry. (‘Rome’ 15)

In May of 1966 A.C. Lyles was presented with the Golden Spurs award for his “extraordinary contribution to western lore, through the medium of films”. His latest production, Waco (directed by Springsteen from a Steve Fisher screenplay) received its world premiere at the Reno Rodeo in June, with stars Jane Russell, Wendell Corey and Brian Donlevy promoting the film by co-marshalling the rodeo’s parade. Putting a little more effort than usual into promoting a Lyles’ film, Paramount even released a single of Lorne Greene singing the title song. Variety was not impressed by the film, calling it a “run of the treadmill western” and singling out Howard Keel for “Particularly bad acting”.

In New York, it appeared in a saturation showcase of over seventy screens, including two first runs. According to Robert Evans, the main feature Assault on a Queen was so poor they had to get rid of it as quickly as possible. (167) Interestingly, Waco represents the only Lyles film to receive a feature-only booking in Variety’s listings. In Minneapolis it managed a week for a ‘small’ take of $4000.

From this point, Lyles’ westerns received fewer first-run North American screenings. Paramount was heavily investing in production and increasing its European dealings. From 1966-9 over half of the studio’s releases involved foreign investment, but even domestically production was increasing. Sixty-five films were released in just 1967-8 and A.C. Lyles was no longer the only low budget independent producer at Paramount. Horror specialist William Castle and family filmmaker Ivan Tors had also joined the lot and their films were often taking the places of Lyles’ westerns on double-bills around the country. For the first two years of his contracts, A.C. Lyles managed to fill some gaps in Paramount’s bare production slates. Now, with a new management team in place, committed to increased production (with the capital to follow through on such promises), the need for Lyles and his films was no longer imperative. (Dick 167-188)

Red Tomahawk, filmed in May of 1966 was another Springsteen directorial effort form a Fisher screenplay. It opened in January of 1967 and it took until July to register its third (and seemingly last) first run supporting engagement. However, in February Red Tomahawk, did ‘big’ business in Detroit, supporting the ‘Jewel Box Revue’ live music act.

Red Tomahawk, filmed in May of 1966 was another Springsteen directorial effort form a Fisher screenplay. It opened in January of 1967 and it took until July to register its third (and seemingly last) first run supporting engagement. However, in February Red Tomahawk, did ‘big’ business in Detroit, supporting the ‘Jewel Box Revue’ live music act.

Filmed in July of 1966 as “Fort Siege”, Fort Utah was Lesley Selander’s 150th feature film as a director, a fact suggested as a selling point in the film’s pressbook, along with such promotional ideas as having men in western garb stroll the city streets, their backs adorned with signs “which plug and credit the film, as well as your theatre and playdate”.

Yet apart from a solitary engagement in Cincinnati in September of 1967, it appears that there were no other first run theatres wanting to accept the film.

By this time Lyles already had two other films completed – Huntsville and Buckskin. Although it would appear that Lyles films were no longer making an impact in the United States, they presumably must have continued to do well in overseas territories, as Paramount extended his deal again, for a further ten films. The first of these, Bushwhackers, was due to film in December of 1967, but the fact that the next scheduled production was an espionage drama titled Rogues’ Gallery shows that Lyles (and Paramount’s) thoughts had moved from the western to other exploitable genres. Rouges’ Gallery was made, but released directly to television. (‘lyles no time’ 3) ( For the second run marketplace where Lyles now appeared to be working, he had to compete not only with American films (studio and independent) but also imported fare. When he began his cycle in 1963 his films appeared curiously nostalgic, four years later, with violent Italian westerns now an accepted part of the cinema mainstream and with Sam Peckinpah on pre-production on The Wild Bunch, Lyles’ ‘oaters’, having changed little over the course of a dozen productions, must appeared as anachronistic relics of a long-gone era. Lyles had mentioned that “Saddle Fire” was due to be filmed in mid-1968. It never eventuated. Nor is it clear whether an announced illustrated dictionary of western slang to be compiled by Lyles and accompanied by a television special ever materialised. (‘inside stuff’ 18)

Huntsville was retitled Hostile Guns and although it is difficult to locate an American release date, an unfavourable review in Variety in July of 1967 would indicate it played in cinemas around that time, nearly a year after it was filmed. Yet another Springsteen / Fisher collaboration and as per usual the key selling points for the film were its star cas

Huntsville was retitled Hostile Guns and although it is difficult to locate an American release date, an unfavourable review in Variety in July of 1967 would indicate it played in cinemas around that time, nearly a year after it was filmed. Yet another Springsteen / Fisher collaboration and as per usual the key selling points for the film were its star cas

t. In February of 1968 Variety complained of studios no longer previewing second feature films for the press and that their reviewers were forced to seek them out on general release (Byron). One of the titles mentioned was Arizona Bushwhackers (formerly Bushwhackers), which they found playing in a “42nd street grindhouse”. An investigation of the New York newspapers of the time failed to locate the cinema and nor does there appear to be any engagements listed for the film at all. The last American film to be directed by Lesley Selander, the pressbook offers ad copy stating the film was the “veteran director’s latest hit!” The screenwriting duties were undertaken by Steve Fisher and the pressbook also maintained that Arizona Bushwhackers was “free of western clichés!” It is doubtful such a description has ever been sincerely used – then or now – about an A.C. Lyles western.

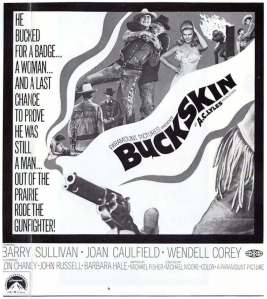

The final Lyles western, Buckskin, was reviewed in May of 1968 in Variety and like the previous two releases, appears tohave had scant distribution in the United States. Buckskin was directed by Michael Moore (a former editor with mostly television direction experience) from a screenplay by Michael Fisher, the son of regular Lyles’ writer, Steve. Although shot back-to-back with Arizona Buswhackers, Buckskin was the first completed of the pair, yet inexplicably, the last released.

THAT’S A WRAP.

Paramount sold the Lyles output to television among various film packages in the late 1960s – early 1970s. By then it was estimated that an adequate quality film, suitable for prime-time broadcast, could potentially earn a million dollars by the time in was sold for syndication. (‘western fare’ 7) With their well-known casts, lack of violence and sex and a general tele-visual aspect, the Lyles westerns were suited to small screens throughout the next decade. With such potential evident by the mid-1960s it is possible to surmise that Paramount continued producing the Lyles westerns with such a future market in mind. When Robert Evans arrived at Paramount he stated that there were eight studios in Hollywood and Paramount were ranked tenth. (‘Confessions’ 83) By 1970, when The Godfather became the highest grossing film of all time and won the studio their first Best Picture Oscar since 1952, the company was back at number one and the Lyles westerns were long forgotten.

But for a few years they helped an ailing studio survive.

If this post has succeeded in its aims it has explained not only the reasons for why the Lyles films were produced, but it has also placed them at the locus of several divergent streams of a troubled industry, proving that the film industry (production distribution and exhibition) is never static.

For an industry once finely attuned to the most acute demands of the ticket-buying public, the 1960s found Hollywood now uncertain of its audience and with little idea how to locate it. In the case of the Lyles’ westerns it was a matter of seeking offshore viewers – those still appreciative of classical genre product. Yet, for their domestic release Paramount were still attempting to find the lost audience and with scant success, tacking these low-budget features onto the tail of a variety of productions and only finding an acceptable market in the form of showcase exhibition.

Yet although their merits as artistic endeavours are debatable for forums elsewhere, the Lyles westerns remain an important exhibit of a tumultuous period, their humble aesthetic belying the desperate measures that necessitated their production, creating one final gasp of the traditional Hollywood western when the rest of Hollywood had bid it farewell.

THE LYLE’S WESTERNS – MAJOR CAST MEMBERS AND

BRIEF PLOT SYNOPSES

Stage to Thunder Rock (1964: William F. Claxton) starring Barry Sullivan, Marilyn Maxwell and Scott Brady. Plot: Sheriff tried to keep a bank robber under guard in a stagecoach station full of people eager to steal the loot.

Young Fury (1965: Christian Nyby) starring Rory Calhoun, Virginia Mayo and William Bendix. Plot: Fugitive finds his son is part of a young gang terrorizing a town. He must stop them.

Town Tamer (1965: Lesley Selander) starring Dana Andrews, Pat O’Brien, Terry Moore and Lon Chaney Jnr. Plot: After his wife is killed by a bullet meant for him, a gunman declares war on the killers.

Black Spurs (1965: R.G. Springsteen) starring Rory Calhoun, Terry Moore, Linda Darnell and Scott Brady. Plot: A bounty hunter finds redemption by cleaning up a corrupt town.

Apache Uprising (1966: Springsteen) starring Rory Calhoun, Corrine Calvet, John Russell and Lon Chaney Jnr. Plot: When he decides to ride shotgun on a stagecoach, a gunman must contend with robbers, corrupt businessmen and rampaging Indians.

Johnny Reno (1966: Springsteen) starring Dana Andrews, Jane Russell, Lyle Bettinger and Lon Chaney Jnr. Plot: A marshal captures a fugitive and takes him to town. He finds the man is innocent and the real villains are the local landowner and his cronies. They are determined to kill the framed man, the marshal determined to save him.

Waco (1966: Springsteen) starring Howard Keel, Jane Russell, Wendell Corey and Brian Donlevy. Plot: Townsfolk release a gunman from jail to protect them from a gang that are terrorizing them.

Red Tomahawk (1967: Springsteen) starring Howard Keel, Joan Caulfield, Broderick Crawford and Wendell Corey. After the massacre at Little Big Horn, a government agent rides into nearby Deadwood to warn them of impending attack. Finding Gatling guns in the town, he tries to get them to a besieged cavalry platoon.

Fort Utah (1967: Selander) starring John Ireland, Virginia Mayo, John Russell and Scott Brady. When a mutinous cavalry sergeant incites Indians to attack a fort, a couple of westerners team up to defend the women inside and capture the troublemaker.

Hostile Guns (1967: Springsteen) starring George Montgomery, Yvonne De Carlo, Tab Hunter and Brian Donlevy. Plot: A veteran marshal enlists a hot-headed deputy to help him transport a coach of prisoners across Texas. The brother of one of the convicts is in pursuit.

Arizona Bushwhackers (1968: Selander) starring Howard Keel, Yvonne De Carlo, Scott Brady and Brian Donlevy. Plot: Due to his civil war past, a gunman is shunned in an Arizona town. However he succeeds in keeping the law.

Buckskin (1968: Michael D. Moore) starring Barry Sullivan, Joan Caulfield, Wendell Corey and Lon Chaney Jnr. A widowed marshal travelling with his half-Indian son confronts prejudice as he attempts to stop a ruthless mine-owner from damming a town’s water supply.

Buckskin (1968: Michael D. Moore) starring Barry Sullivan, Joan Caulfield, Wendell Corey and Lon Chaney Jnr. A widowed marshal travelling with his half-Indian son confronts prejudice as he attempts to stop a ruthless mine-owner from damming a town’s water supply.

LEADING PLAYERS IN LYLES’ WESTERNS

NOTE: The second column header, ‘LW’ stands for the number of Lyles’ westerns the performer appeared in.

-

All of the performers made numerous guest appearances in television series. Those listed are where the performer had an ongoing leading role.

-

The final column only intends to provide a brief description to when the performer was most popular and the level of fame they achieved.

RECURRING OR NOTABLE SUPPORT PLAYERS IN

LYLES’ WESTERNS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“A.C. Lyles Begins 10 for Par, Never heard of Freud but loyal to Dick Arlen and Virginia Mayo.” Variety 26th July 1967: 5.

“A.C. Lyles Begins 10 for Par, Never heard of Freud but loyal to Dick Arlen and Virginia Mayo.” Variety 26th July 1967: 5.

“A.C. Lyles contracts ten tinters with Paramount.” Variety April 24 1965: 7.

Archer, Eugene. Rev. of Law of the Lawless, By William F. Claxton. New York Times 27th August 1964: 17.

Archer, Eugene. Rev. of Black Spurs, By R.G. Springsteen. New York Times 29th May 1965: 17.

Arizona Bushwhackers: Paramount Merchandising Manual and Pressbook. [USA] Paramount Pictures Corporation And A.C. Lyles Productions, 1967.

Boddy, William. “Sixty Million Viewers Can’t Be Wrong: The Rise And Fall Of The Television Western.” Back In The Saddle Again: New Essays On The Western. Ed. Ed Buscombe & Roberta E. Pearson. London: Bfi, 1998. 119-141.

Black Spurs: Paramount Merchandising Manual and Pressbook. [USA] Paramount Pictures Corporation And A.C. Lyles Productions, 1964.

Buckskin: Paramount Merchandising Manual and Pressbook. [USA] Paramount Pictures Corporation And A.C. Lyles Productions, 1968.

“Big Picture Rentals of 1960.” Variety January 4th 1961: 6 & 36.

“Big Picture Rentals of 1961.” Variety January 8th 1962: 7 & 53.

“Big Picture Rentals of 1962.” Variety January 5th 1963: 5 & 60.

“Big Picture Rentals of 1963.” Variety January 1st 1964: 5 & 74.

“Big Picture Rentals of 1964.” Variety January 7th 1965: 7 & 39.

“Big Picture Rentals of 1965.” Variety January 2nd 1966: 9 & 57.

“Big Picture Rentals of 1966.” Variety January 5th 1967: 11 & 97.

“Big Rental Films of 1967.” Variety January 3rd 1968: 19

“Big Rental Films of 1968.” Variety January 4th 1969: 17 & 29

“Big Rental Films of 1969.” Variety January 7th 1970: 15

“Brief Encounters on RKO Tactics for Par’s Summer Doubles.” Variety March 26th 1965: 25.

Buscombe, Ed. “The Western: A Short History.” The BFI Companion To The Western. Ed. Ed Buscombe. London: Andre Deutsch, 1988. 36-7.

Byron, Stuart. “Torpedo Trade Reviewing: Second Feature Rarely Shown.” Variety February 21st 1968: 7, 28.

Coyne, Michael. The Crowded Prairie: American International Identity in the Hollywood Western. London: I.B. Taurus, 1997.

‘Dale’. “Stage to Thunder Rock (review)” Variety June 10th 1964: 6.

Davis, Ronald L. Hollywood Beauty: Linda Darnell and the American Dream. Norman: University Of Oklahoma, 1991.

Dick, Bernard F. . Engulfed: The Death of Paramount Pictures and the Birth of Corporate Hollywood. Lexington: University Press Of Kentucky, 2001.

Eames, John Douglas. The Paramount Story. London: Octopus, 1985.

Evans, Robert. “Confessions Of A Kid Mogul.” Anatomy Of The Movies. Ed. David Pirie. New York: Macmillan, 1981. 80-87.

Evans, Robert. The Kid Stays in the Picture. New York: Hyperion, 1994.

“Evans’ ‘Sleeping giant now awakes’ – Par’s holly and product in pep rally.” Variety [New York ] Nov 16 1966, 3.

Finler, Joel W. . The Hollywood Story. London: Pyramid, 1989.

Flynn, Charles & Todd McCarthy. “The Economic Imperative: Why Was The B-movie Necessary?.” King Of The B’s: Working Within The Hollywood System. Ed. Todd McCarthy & Charles Flynn. New York: E.p. Dutton , 1975. 13-44.

Fort Utah: Paramount Merchandising Manual and Pressbook. [USA] Paramount Pictures Corporation And A.C. Lyles Productions, 1966.

Gomery, Douglas. Shared Pleasures. Madison: Universty Of Wisconsin Press, 1992.

Gomery, Douglas. The Hollywood Studio System: A History. London: Bfi, 2005.

Heffernan, Kevin. Ghouls, Gimmicks and Gold: Horror FIlms and the American Movie Business 1953-1968. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

Hostile Guns: Paramount Merchandising Manual and Pressbook. [USA] Paramount Pictures Corporation And A.C. Lyles Productions, 1967.

“It’s Not Art, But….” Time 6th August 1945: 34-5.

Holben, Jay & Douglas Bankston. “Inventive New Options for Film.” American Cinematographer Feb 2000: 96-107.

“Inside Stuff – Pictures.” Variety August 2nd 1967: 18.

Izod, John. Hollywood and the Box Office: 1895-1986. London: Macmillan, 1988.

Joyner, C. Courtney. “A.C. Lyles: Gentleman of the West.” Wildest Westerns Collectors Edition #3 2001: 44-50.

Kalish, Eddie. “Anyone Else for Showcase?.” Variety December 11th 1963: 3.

Kalish, Eddie. “Quickend outside production deals for Par. studio now likely.” Variety 24th June 1964: 3.

Kalish, Eddie. “Double bills strike back or: the return of the dualler.” Variety July 7th 1964: 7

‘Kash’. “Arizona Bushwhackers (review).” Variety May 16th 1968: 8.

Law of the Lawless: Paramount Merchandising Manual and Pressbook. [USA] Paramount Pictures Corporation And A.C. Lyles Productions, 1963.

Loy, R. Philip. Westerns in a Changing America: 1955-2000. Jefferson: Mcfarland, 2004.

Marks, Ed. “From Lawmen to Lepus: An interview with A.C. Lyles.” Filmfax #117 June 2007: 41-7.

Monaco. History of American Cinema: The Sixties. Volume 8. 10 vols. New York: Gale Group, 2001.

Neale, Steve. Genre and Hollywood. London: Routledge, 2000.

“Nix westerns-Smith. Too inflated: Gotta load ’em with Stars.” Variety [New York ] Jan 8th 1964, 13.

“Oaters profitable overseas, so Par gives reins to Lyles.” Variety November 20th 1963: 3.

“Par takes turn at showcase bat with ‘Stranger’ via 2 first runs then 20 theatre expansion.” Variety June 29th 1964: 5.

Puttnam, David. The Undeclared War: The Struggle for Control of the World’s Film Industry. London: Harper Collins, 1997.

Red Tomahawk: Paramount Press Book and Merchandising Manual. [USA]

Paramount Pictures Corporation and A.C. Lyles Productions, 1966.

“Rome Wickets Hip for Oaters .” Variety June 19th 1967: 7.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System. New York: Metropolitan, 1988.

“Showcasing: What is a studio to do?.” Variety 12th May 65: 3.

Slotkin, Richard. Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth Century America. New York: Harper Collins, 1992.

Stanfield, Peter. Hollywood, Westerns and the 1930s: The Lost Trail. Exeter: University Of Exeter Press, 2001.

Town Tamer: Paramount Merchandising Manual and Pressbook. [USA] Paramount Pictures Corporation And A.C. Lyles Productions, 1965.

‘Tube’. “Law of the Lawless.” Variety March 25th 1964: 6.

Tuska, John. The Filming of the West. New York: Doubleday, 1976.

“US Westerns Went Thataway: To Europe.” Variety September 18th 1963:

Waco: Paramount Merchandising Manual and Pressbook. [USA] Paramount Pictures Corporation and A.C. Lyles Productions, 1966.

“Western Fare Prime for Network Skeds.” Variety March 3rd 1968: 17.

White, Timothy R.. “Hollywood’s Attempt At Appropriating Television: The Case Of Paramount Pictures.” Hollywood In The Age Of Television. Ed. Tino Bailo. Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1990. 115-145.

You must be logged in to post a comment.